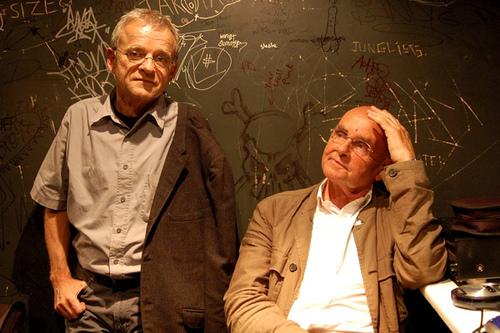

Dieter Moebius & Hans Joachim Roedelius, London 2007 [photo: Mark Pilkington]

With the reformed Harmonia playing their first live gigs in over thirty years, it seemed like a good time to online this piece I wrote for Plan B magazine.

It appeared in their 30th issue, Feb 2008.

Cosmic Outriders: The Living Music of Cluster and Harmonia

by Mark Pilkington

From immense kosmische dronescapes to sugar-rush rhythms and merry electromelodies, it’s almost impossible not to find traces of their unique sound in contemporary electronic music, whether you’re listening to the fairground ditties of Plaid and Boards of Canada, or the wilful experimentation of Autechre, Nurse With Wound or Matmos. Yet almost 40 years after their first performances, there are still far too many people out there who haven’t heard the music of Kluster, Cluster and Harmonia.

Dieter Moebius and Hans Joachim Roedelius: London 2007 [photo: Mark Pilkington]

April 2007

Seated across a functional tabletop, their faces betraying calm but deeply focused intensity, their bodies still save the occasional movement of their hands, which make small deliberate gestures, the two men, older if not old, might be playing chess at a pavement café in Vienna or Berlin.

Instead they are onstage at a Metal-stained London rock venue, bathed in red light before a rapt audience of two hundred geeks and gawkers. The table is neatly strewn with cables, CD players, mixers and a small synthesiser whose combined outputs fill the room with squelches, squawks, womms and wibble; warm, fluid pulsations that might be bathospheric recordings from within a vast, bio-mechanical whale.

At the helm are Hans Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius, tonight they are Cluster, and together they form a critical axis of the unspoken history of late 20th century experimental music.

Rewind 39 years to a back room of the Schaubühne theatre-bar in West Berlin. Here Roedelius, a 35-year-old masseur who has drifted into the city’s burgeoning experimental music community, and Conrad Schnitzler, 32, a student of the artist-visonary Joseph Beuys and the scene’s maestro, run the Zodiak Free Arts Lab. The Zodiak is a haven for freaks and avant-gardists to enjoy psychedelia, free-jazz, free performance and freakout; a venue and practice space and, as the birthing ground for Tangerine Dream (of which Schnitzler was also a founder member) as well as Kluster, a galactic centre for Kosmische Musik.

The Zodiak was the centre of a musical revolution in a country teetering on the edge of a political revolution, but for Roedelius, now a kind, dome-headed, twinkly-eyed but still imposing 70-something-year-old, the politics of the Zodiak were purely the politics of the imagination, a place to channel the madness outside into performance and sound. It’s an attitude that is quite understandable from one who had survived being press-ganged into the Hitler Jugend at 11, getting caught up on the Russian front in WWII, spending two years in a Stasi labour camp and, later, babysitting for the Baader-Meinhof crowd. Having seen the tumultous effects of political revolution at first hand, something that most of his Zodiak contemporaries had experienced only through its aftermath, Roedelius wasn’t sure if West Germany needed another one.

Schnitzler, however, was a very different animal. Known as something of a wild man even in the anarchic foment of late ’60s Berlin, Con was had for some time been creating obtuse and abstract ‘chamber’ music as Noises and Plus/Minus, drawing in accomplices including Roedelius, who also performed with the eight-piece gestalt-rockers Human Being, and solo, with ‘a microphone, a handmade flute and an alarm clock’. Amongst those digging the Zodiak sounds was another young student of Beuys (and then a steakhouse chef), Dieter Moebius. ‘One day in 1969, Achim and Conny asked if I wanted to join a group called Kluster,’ says Moebius, a spry, wiry and impish 63-year-old; ‘a few days later, on 17 July 1969, we were performing a 12 hour concert in an art gallery above a Berlin shopping centre.’

Early performances, which were – and still are – always improvised, had the trio operating in dense but open-ended cacophanous driftspace, employing modified cellos, guitars, flutes, microphones, tape machines, organs, percussion and whatever else they could find to open aural doorways into otherness. For Schnitzler it was art and performance, for Moebius it was ‘some kind of music,’ but for Roedelius it was something more complex and personal: ‘after the horrors of my childhood, it was all about coming back to normal, a process of becoming aware of myself. So it was art and music, but first a sort of self-finding.’ It wasn’t a pretty sound, or even a pleasant one, and it was certainly a world away from the already-traditional r’n’b-based psychedelic music of the imported British and American rock groups, which would be aped by many of the German bands that were later dubbed ‘krautrock’. Yet Kluster had it’s own captivating structure, beauty and undeniable majesty and, in the spirit of a difficult age, the small audiences to their twelve gigs were largely enthusiastic.

A few months later, having relocated themselves, their equipment and their girlfriends to Dusseldorff, where Schnitzler was able to fix them up with more gallery and artspace shows, Kluster were ready to record. Funding for the studio session that produced their first two albums Klopfzeichen (‘tapping’ or ‘knocking’ signals) and Zwei-Osterei (‘Two Easter Eggs’) came from Oskar Gottlieb Blarr, a church organist with a passion for avant garde music. The records were released on the religious Schwann label, with the proviso that they contained Christian content. Hence the first sides of both albums are accompanied by dramatically-declaimed agit-poetry and spiritual admonition. It’s a strange way to start an avant garde musical career, though what comes around goes around and Roedelius would convert to Catholicism in 1984.

Keeping with the religious metaphor, it might be fair to describe the initial Kluster albums as an LSD-dipped tour through the circles of post-war hell: car batteries buzz, oil barrels clang and marbles roll around in a bowl, accompanied by cello, flute, guitar feedback and organ drones, to create a seething topographic dissonance that stretches from Edgar Varese on one horizon to the Velvet Underground on the other. This potential audio catastrophe was given shape and form by the young studio engineer Conrad ‘Conny’ Plank, who had previously worked with Varese and would later produce many seminal Kosmische bands, including Neu!, Kraftwerk, Ash Ra Tempel and Guru Guru, then avant-pop acts like Devo, Eurythmics and Ultravox until his death in 1987, aged 47. Moebius and Roedelius both refer to Plank as a third member of Cluster, and a dear friend.

By 1971 Kluster were beginning to make a name for themselves on the underground, but Schnitzler was ready to pursue life as a solo musician and artist. Moebius and Roedelius, however, were just getting started. The change in line-up required a new name, but their attitude, and their sound, remained much the same.

So, Kluster became Cluster and, along with their now-friend Conny and a mongrel dog named Stinky, they continued in their mission. Their first album, Cluster, was released by Philips, who were quick to get hip to West Germany’s newly evolving ‘kosmische’ (cosmic) sound, and presents the trio (Plank produced once again) evolving at a glacial pace. Cluster is, if anything, even darker than its predecessors, with a harsher, more abrasive and electronic sound evoking colossal forges and tectonic shifts. Cluster II, recorded for the then-trendy Brain label, transfers the field of operation from the bowels of the Earth into the cold, dark eternity of outer space.

All Cluster’s work has the feel of something alive being channelled and shaped by human hands rather than being created, and with these two albums, devoid of voice and language, the sense of human origins is almost entirely absent. This wan’t necessarily their intention, nor was there any plan, recalls Roedelius, ‘we were just experimenting all the time to find out in which way the music would develop itself.’

Living out of a van and gigging intensely and extensively – including an unlikely, uncomfortable night at Germany’s first open air rock festival, Fehmarn, where Jimi Hendrix gave his final performance – was beginning to take its toll on the dissonant duo, with drugs and alchohol becoming a regular part of their line up. Relief came in 1973, when Roedelius and Moebius were invited to join an intentional community that had taken over a village, Forst, in the wooded idyll of Lower Saxony. Here, free from the industrial confines of the city, Cluster was to undergo a dramatic, entirely unexpected mutation and sonic hell was to become sonic heaven.

November 2007

Dieter Moebius, Hans Joachim Roedelius, Michael Rother: Berlin 2007 [photo: Mark Pilkington]

In the grandiose, elegant surroundings of Berlin’s Haus der Weltkulturen, whose collapse is said to have given Einsturzende Neubauten their name, Roedelius and Moebius appear small on the huge open stage, where they are joined by a third mind. Looking like a dapper, suntanned cross between David Hasselhoff and Roger Waters is the man who changed their muscial world – Michael Rother.

While Rother and Moebius have been performing live together for a few years now, it’s the first time that Harmonia have played as a trio in 31 years and their collaboration, improvised as ever, is a world away from the organic machine room groove of Cluster’s earlier 2007 performance. As images of their youthful selves are projected behind them, the tidy trio, along with a choir conducted by diva-electronica Barbera Morgenstein, generate a sparse, warm and very human atmosphere of Zen flow. Sampled chimes, gongs and bells ring out between the pads, plips and pulses: Moebius and Roedelius pore over samplers and CDs while Rother drops in simple but ectstatic digital rhythms and, ever so sparingly, taunts us with gliding, beautific but never saccarine guitar.

It’s a long performance, filled with bold silences and not-quite-empty space, providing ample room for contemplation. As the men they were thirty years ago drift and swirl overhead, we consider the impermanence of all things and the problems with keeping up with oneself. No body, and no band, can ever compete with the heights of their own creative life, the moments when chance, time and chemistry give rise to brilliance. But, a couple of karaoke moments aside, when the band are literally playing with themselves over greatest hits, Harmonia don’t try. Why should they? In a quieter moment someone from the audience yells ‘ambient!’ – as if it were a bad thing. And as if Harmonia hadn’t invented Brian Eno…

Forst, 1973

Seeking respite from the intensity of being one half of Neu! and a key player in the first incarnation of Kraftwerk , after recording the troubled second Neu! album Rother took himself and his instruments out to the pastoral idyll of Forst. Here life was as much about cooking, strolling and chopping wood as it was about music, and the trio discussed the potential of a new sound, one that would take the Cluster hallmarks of unearthliness and improvisation and meld them into something that was, well, pop music, at least compared to anything heard from Cluster thus far.

What followed are three of the most wonderful albums in the entire krautrock canon.

‘Watussi,’ the opening number from 1974’s Musik Von Harmonia, with its absurdist pop-art cover depicting a colossal bottle of detergent (the new name Harmonia combined harmony and ammonia), sets the tone with Roedelius’ relentless contra-rotating arpeggiations played out against tidal guitar drones and Moebius’ controlled detonations of electronic scatter, all layered over Rother’s primitive, stomping drum machine rhythms. The album presents a beautiful, alien world awash with colours and sounds unseen and unheard on our own planet. Breezes blow inverted rainbows across azure leaves, dark shapes glide through cyan shimmering waters, maddening rubber melodies flow like swarming caterpillars. Later, on ‘Ahoi!’, the track which would become at least one Eno album, a delicate stillness takes hold, shaped only by gently plucked guitars and distant organ swells. Recorded at Cluster’s Forst studio and only modestly tweaked by Conny Plank in Colgone, Musik Von Harmonia remains fresh, exciting and extremely daft, with a strange, laid back charm that is rarely matched by today’s clean and quantized electronicists.

A recently uneathed live recording of Harmonia in 1974 captures a more unruly, though no less engaging, picture of the band, with Rother soloing his way into the stratosphere over the unending crunch and thud of drum machines and ever-spinning organ ditties. It was around this time that Brian Eno would seek out the group, joining them for sessions some time later that resulted in the album Harmonia 76: Tracks and Traces as well as Cluster & Eno, After The Heat and the track ‘By This River’ on Eno’s Before And After Science. The Eno and Cluster/Harmonia collaborations make for intriguing avant-rock history, and contain many serene and haunting moments. They may not have resulted in any of the team’s best work, but it’s quite clear to hear that each influenced the other, particularly listening to Eno’s later ’70s music.

Within months of recording as Harmonia, entranced by the rhythmic and melodic vistas opened up to them by Rother (who gets co-production credit on the album), Moebius and Roedelius got back to work as Cluster to produce Zuckerzeit (Sugartime). What for many is their masterpiece is worlds away from the darkness of their previous records. Retaining the glistening plasticity of Musick Von Harmonia, Zuckerzeit once again reflects the duo’s new country existence in an album rippling with melodic beauty, uninhibitedly draped over endearing, ungainly rhythms and occasional dissonant morasses that hark back to the earlier Kluster sound. As the name suggests, Zuckerzeit is almost all sweetness and light, never more so than in the fluid, ecstatic melodies of ‘Rosa’, named for the birth of family Roedlius’ first daughter. The wonky groove of ‘Caramel’ could be the soundtrack to a far corner of Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, while ‘Rote Riki’ sounds like exercise time at a Clanger nudist colony. With hindsight, the seeds of myriad future electronic musics burst free from these two records, yet between them they sound not just unlike any other albums produced by the team, but unlike any other albums ever made.

Having completed contractual duties with the ever-stressful Neu!, Rother returned to Forst and, as Harmonia, the team produced another miracle of an album, 1975’s De Luxe. After the DIY-kronkiness of Musick Von and Zuckerzeit, the sheer majesty of De Luxe is astounding. If those albums are gingerbread houses then De Luxe is a country manor – one that is infinitely larger on the inside than it could ever be on the outside. The eponymous nine-minute opening track alone rages with incandescent, cosmic glory while still sounding like a goofily anthemic German drinking song. ‘Walky Talky’ brings Guru Guru’s wildman drummer Mani Neumauer into the mix for a rolling surfboard ride through the ionosphere, and then they pull off seven minutes of absurd parallel universe stadium rock with ‘Monza’. Three tracks later, the album touches down gently with the lilting, frogs’n’ivories closer ‘Kekse’ and you’re left wondering why the hell it took 30 years for De Luxe to get a CD release.

Having completed contractual duties with the ever-stressful Neu!, Rother returned to Forst and, as Harmonia, the team produced another miracle of an album, 1975’s De Luxe. After the DIY-kronkiness of Musick Von and Zuckerzeit, the sheer majesty of De Luxe is astounding. If those albums are gingerbread houses then De Luxe is a country manor – one that is infinitely larger on the inside than it could ever be on the outside. The eponymous nine-minute opening track alone rages with incandescent, cosmic glory while still sounding like a goofily anthemic German drinking song. ‘Walky Talky’ brings Guru Guru’s wildman drummer Mani Neumauer into the mix for a rolling surfboard ride through the ionosphere, and then they pull off seven minutes of absurd parallel universe stadium rock with ‘Monza’. Three tracks later, the album touches down gently with the lilting, frogs’n’ivories closer ‘Kekse’ and you’re left wondering why the hell it took 30 years for De Luxe to get a CD release.

Even within the wildly unpredictable krautrock universe, and the narrow social confines of the music scene of the time (Roedelius went out with Florian Schneider from Kraftwerk’s sister for a while) Cluster and Harmonia were just, well, different. Says Roedelius: ‘we didn’t fit into the category Krautrock at all, because we weren’t part of it, even though it was said that we were. We didn’t care, we belonged to the artscene as well as to the popular music-scene, Cluster was always special.’

And they still are.

Harmonia recorded one more album, Harmonia 76: Tracks and Traces, this time with Brian Eno, though Rother left half way through the session and the album, more a collection of sketches, didn’t see the light of day until 1997. Despite a couple of standout tracks, like the chuggingly intense motorik ‘Vamos Campaneros’ and the synth-and-guitar-at-play field recordings of By the Riverside, the title mostly reflects the contents, being either a half-finished Harmonia record, or a half-finished Eno record – it’s hard to tell which.

This fertile period did produce one more classic Cluster record, Sowiesoso (1976). Allegedly recorded in two days, it comes across as if Forst’s woodland entities had taken over the studio entirely; devas on the drum machines, lambs gamboling on synthesisers (probably used here for the first time, though when asked, Moebius replied ‘if only I knew’) and fauns geting frisky with effects boxes. The rhythms are more subtle and dynamic while its pacing is provided by water flowing over rocks and wind through trees. If the album isn’t as immediately captivating as the previous Forst recordings, it will slowly change your mind for you until you realise that it’s as beautiful as a misty woodland morning in Spring.

Together and separately, Dieter and Hans Joachim’s musical journeys continued through the ’80s, ’90s and ’00s, with Roedelius still producing new work at a formidable rate, but here, backlit by sunshine amongst the trees and the breeze, we must leave them and return, heads and hearts thrumming with earth and electricity, to the present day…

If a band could feed off namechecks and tributes alone, then Moebius, Roedelius and Rother would sport bellywheels by now, but commercial success was never on the cards for such timeless music. Roedelius admits that without his wife’s income as a teacher, he would not have been able to support himself while, when not making music; Moebius worked on film and TV props for his wife’s company.Moebius is honest about seeing contemporaries like Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream hitting the international bigtime, ‘I was quite jealous!’ Roedelius, ever the artist, remains circumspect: ‘There’s not much I have to say about it, after all that I had to go through myself. Each of us has his own personal domain in life, his obligations and his limits.’

To listen to Cluster and Harmonia is to undertake a strange adventure through times, sounds and spaces that can, by their very improvised, instantaneous nature, never exist again. Their best music seems to be composed entirely of juxtapositions – bold simplicity and fiendish complexity, atonal dissonance and harmonius beauty, elegant sophistication and pratfall foolishness – contrasts personified in Roedelius and Moebius themselves. It’s a magic that can never be undone.

‘We had to learn to become aware of what we did while doing it,’ muses Roedelius, ‘but there was always a special chemistry between Moebius and me from the beginning. We’ve been friends for almost 40 years now. We’ve been through bad periods of course as well, but our friendship has never broken. We just loved to do what we did, we never were after success.’ Having witnessed the horrors or war, the chaos of its aftermath and the incredible rebirth of culture that took place in his native land, Roedelius is a man who has lived through the very worst and the very best that humanity has to offer. Seeing him now, performing two hour concerts in his seventies and DJing ’til the wee hours at his own afterparty, it’s easy to believe him when he says ‘I’m just in love with life itself.’

And it really could be as simple as that.

Perhaps it’s the humanity, warmth and, yes, love – in even their darkest hours – that makes the music of Roedelius, Moebius and Rother stand out. And now, almost 40 years on, faced with adulatory crowds, many of whom weren’t born when the music they adore was made, some of that love is paying off. ‘It really is very astonishing to me,’ says Moebius, ‘it makes me happy in a way, but also a little proud.’

Cluster and Harmonia albums are available wherever interesting music can be found.

In 2008, Harmonia are playing festivals the world over. Painting with Sound, a biography of Roedelius by Stephen Iliffe, is available from Meridan Music Guides.